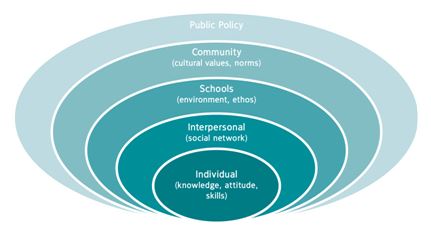

Healthy Teen Network is committed to using the social-ecological health promotion frame (more information in our 2013-2016 Strategic Plan), incorporating the social determinants of health to build collaboration beyond our field and achieve results across diverse populations, including pregnant and parenting teens. But what are the social determinants of health and how do they affect adolescent sexual and reproductive health? Recently I had a conversation with distinguished Professor and Researcher, Dr. Ralph DiClemente, to hear his take on this subject.

For the benefit of those who are not familiar with the concept, how would you define the social determinants of health?

Ralph DiClemente: I would define the social determinants of health as factors that affect people’s health behavior. They generally refer to any factor or influence external to the adolescent that resides in their community or society. So, you can refer to them as extrinsic factors.

So how would one address these extrinsic factors or social determinants of health in their work?

RD: There are a couple of ways. First, you have to decide at what level these factors are operating. For example, an extrinsic factor could operate at a dyadic or partner level. You could try to develop programs that either get partners into treatment, for example for STDs, or you may do partner interventions. We bring in a young woman and her male partner—this is a dyadic-level intervention.

Other extrinsic factors may operate at the peer network level. So another thing you might try then is community level interventions where you target the entire network of young people and try to change (peer) network norms and perceptions, which leads hopefully to changing network behaviors.

A third level may operate at an organizational level, for example health departments or clinics, in which case you would want to work in those clinics to develop adolescent friendly centers or have adolescent friendly times when only young people are going to be in the clinic… Another opportunity is to move the clinic into the community, for example, mobile vans. We can go to where young people are because, it is less stigmatizing than going to the clinic and young people may not have the means—cars, transportation, money, etc.—to get to clinics. So let’s bring the clinic to them—reduce that barrier—the accessibility.

Another level may be at the broader societal level. These are issues such as poverty, discrimination, both racism and sexism, media influences—how does the media portray adolescents, how does it portray minority youth, how does it portray female minority youth. So there, you may want to engage in media literacy training in schools, get the schools involved in dispelling myths. You can also do social marketing approaches at the broader societal level.

There are a lot of social determinants—you need to determine where they are emanating from, and once you have decided that, then you can target your intervention to that level.

Do you personally target all these different levels of social determinants—partner, peer network, organizational, and societal—in your work?

RD: Well, we try to. And because we are doing research projects, we don’t have unlimited resources, which certainly is a constraint. However, we certainly do try to target all these social determinants. For example, in a more recent study, we developed expedited partner treatment for young women testing positive for an STD, in which case they could actually bring medication to three of their male sex partners. So the male sex partners did not have to go to the clinic.

In doing so you addressed a huge barrier.

RD: Exactly! The barrier of time, cost, and the argument that often ensues from young women telling a boyfriend, “You gave me an STD.” Instead they say, “It may not have been you, it may have been you, but here’s some medication. If I have got this, you may have it as well since we had unprotected sex.” So they get treated, it’s good for them, it’s good for the couple, and it reduces the potential spread through the rest of the network. That’s one example of a dyadic approach.

Another example of our approach is the use of media in our interventions. We roll in the media literacy piece in our interventions by playing for example rap music or music videos that show young African American girls in less than a positive light and we critique the lyrics. Many young girls say them, but they haven’t thought about what the lyrics mean. [The lyrics] are misogynistic. But until they read them…and we go through them, they don’t really know what they mean…So we sensitize them to the lyrics and [ask] how does that make you feel to be called this, that, and the other thing. So again, we want to target across multiple levels, because multiple levels are essentially influencing their behavior, creating a fertile ground for risk behavior. The solution we feel is to target multiple levels with interventions we think will benefit young women. And young men for that matter as well.

Would you say the potential for greater impact is why it is so important for the field of adolescent sexual and reproductive health to address the social determinants of health?

RD: Yes, it is clear that by focusing only on young people—young boys and young girls—we are missing a really key piece of the equation, which is the environment in which they exist, the social context in which they exist. No one exists in a vacuum. All of us are influenced to some degree by what we see around us, what our friends and family tell us, how we model other’s behavior whether it’s actual real life behavior of friends or modeling what we see on the TV or internet. So the issue becomes, if all those issues are coalescing to affect our behavior, we need to be able to target those influences to optimize our effects.

For people who are currently implementing, for example, an evidence-based intervention, what are three concrete ways they may be able to address the social determinant of health if they are not already doing so?

RD: Well the first way is to understand those determinants. They may want to ask their young clients to identify sources of influence. So before you can develop an intervention, you really need to do an assessment of the primary sources of influence. (Assuming of course that you do not have unlimited resources…) Once you have identified what those sources are then the next step is to either address those sources in your intervention or address those sources directly—one way is to directly change them.

For example, accessing teen clinics is not easy. Well, you can directly address that by providing young people with transportation resources or having the clinic hold special days for young people or having a mobile van …That would be an easy approach—the direct approach to the social determinant. An indirect approach would be working with the team. Maybe they could touch base with friends, family, etc., to see about getting transportation…. So again, you can directly address these issues–and if you can that’s perfect, or you can try to indirectly address them, or in fact do both.

These are great recommendations and I am sure our readers will benefit greatly from your insight, Dr. DiClemente. Is there anything else you would like to add? Perhaps a question I have not asked you or what we should be thinking about in terms of the social determinants of health?

RD: Well, I think we need to think broadly. We often think about individuals. We have to get out of that mindset and realize that individuals, young people, only exist in a social context. So, understanding that social context is critical. And unfortunately it is a lot easier to focus on the individual and put all the responsibility and burden on them, but that’s not fair. It’s eminently unfair and what we need to do is recognize that we are dealing with young people who have a different maturational level, a different cognitive level, and different resources both cognitive a well as financial.

We need to stop the blame game.

RD: It is a blame game. “You should be doing this!” “You should know better!” Everyone knows better. Adults smoke. They know better. Adults don’t exercise. They know the risk for heart disease and stroke. Adults don’t eat well. Do we blame them? But we blame girls when they get pregnant. We blame kids when they get an STD. I don’t understand the dualism here.

This year at our annual conference Healthy Teen Network is proudly awarding you with the Douglas B. Kirby Researcher of the Year Award.

RD: I’m flattered! That’s major!

Would you please share Doug Kirby’s contribution to the field of the social determinants of health and his legacy?

RD: Well, I think it I hard to quantify what Doug meant to this field in a very short period of time. He was clearly an exemplar of a researcher and how a researcher could be sensitive to the community and work collaboratively with the community. (He was a) very rigorous methodologist, but also sensitive to the needs of people. He wasn’t designing laboratory studies: he was working in people’ homes and communities. He developed a set of guiding principles for effective programs; his reviews are cited repeatedly. For example “No easy answers” is often cited in terms of addressing these issues. He was fair, eminently fair in his evaluation of research, and he was certainly an advocate for young people. [He was a] strong advocate that was beneficial in having programs developed and implemented for young folks. I am delighted, proud, and privileged.

One last question. What do you think we should look forward to seeing and hearing at the conference next month?

RD: I think it is always great to go to a conference with like-minded folks…like-minded not necessarily in solutions, but like-minded in their advocacy and their interest. We want diversity in terms of solutions. We want creativity. We want innovation. Everyone at the conference will have an interest and focus. And that’s great! The feeling, the energy that emanates from that room will be palpable.

How do you address or consider social determinants of health in your work? How have you used media in your interventions? Leave your comments below!

Mousumi Banikya-Leaseburg, MD, MPH, CPH is a Program Manager at Healthy Teen Network.

You must be logged in to post a comment.